Written By: Sadhana Matheswaran

Call: I say “Black Lives”, You say “Matter” Response: Black Lives Matter. Black Lives Matter. Say Her Name. Breonna Taylor. Show me what America Looks Like? This is What America Looks Like. No Justice. No Peace.

These chants began to fill the streets in early June as thousands of individuals around the country protested in support of the Black Lives Matter Movement, demanding Black Lives be recognized through justice, equality, and legal reform. However, the Black Lives Matter protests aren’t new to America. For decades Black individuals have been protesting against systemic racism, an epidemic that has lasted for over 400 years and has affected every aspect of their life.

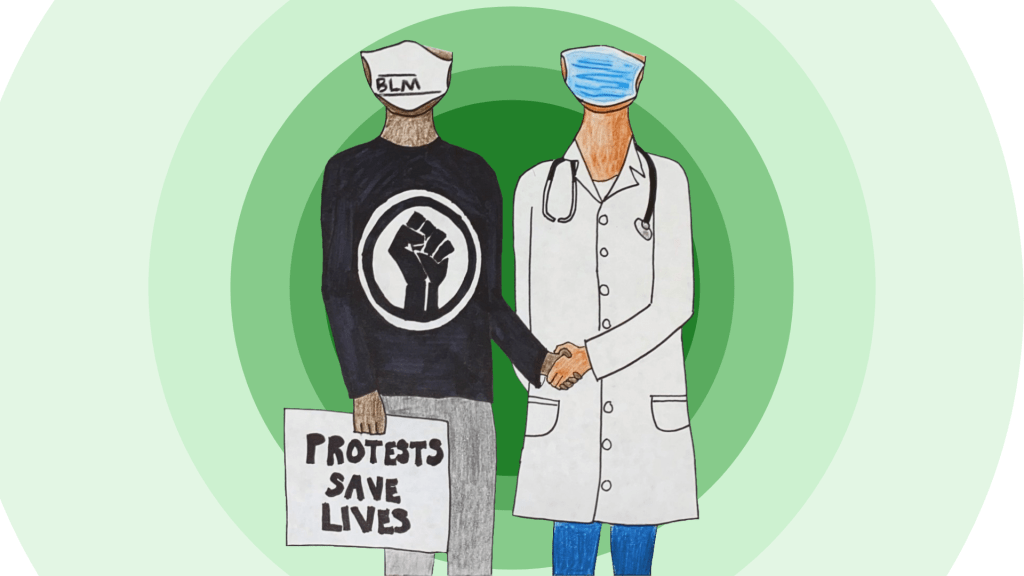

Yet in 2020, Black individuals in America now find themselves bearing the burden of two, “-demics,” one being the unending epidemic of racial injustice and the other being the COVID-19 pandemic. The two are inextricably linked and represent a cruel irony. The racism and inherent inequities that result as a by-product of racial injustice are the same inequities that make Black individuals more vulnerable and susceptible to the COVID-19 pandemic. Protesting then becomes not only vital for demanding change and dismantling systems but also to help save lives and ensure the health, safety, and well-being of Black individuals, especially during this pandemic.

However, many have expressed concerns whether COVID-19 would increase as a result of the protests as it fails to follow basic guidelines such as social distancing. Despite these valid concerns, almost 1200 public health officials wrote an open letter in support of the protests calling them, “an anti-racist public health response to demonstrations against systemic injustice occurring during the COVID-19 pandemic.” The support of public health officials toward the protests may seem to contradict current COVID guidelines. Nevertheless, at the same time, public health officials stress that their support “should not be confused with a permissive stance on all gatherings, particularly protests against stay-home orders.” The seemingly hypocritical statements then raise the questions: What makes the Black Lives Matter protests an exception? Why support the thousands of people protesting on the street when that could possibly worsen the current situation of the pandemic? The resounding answer: Enough is enough. Systemic racism is a public health crisis too, and without action, it will continue to threaten the health of marginalized communities for even more generations to come.

Protesting Despite The Risks

Nevertheless, protesting during a global pandemic comes with its own set of risks. During the peak months of the protests, protestors faced an increased risk of contracting COVID-19 and the risk of bodily injury from violence. Yet these were necessary risks the protestors were willing to take in order to save their lives from the threat of police violence and other structural and systemic inequities. Protestors, however, also faced a backlash from community members and some public health officials who feared the protests would spike COVID-19 infections and exacerbate the current pandemic situation. Ironically, those making such claims seemingly forgot that the majority of individuals protesting came from black and brown communities who had been disproportionately affected by the virus.

To better understand the risks and effects of the protests on the spread of COVID-19, researchers from Northeastern, Harvard, Rutgers, and Northwestern collected surveys and data from cities that reported high rates of participation in protests. After significant study, the researchers concluded that “there was a clear and significant negative correlation between the percentage of a state’s population who reported protesting and the subsequent increase in cases of COVID-19.” In other words, the protests were unlikely to have directly caused the increased rate of COVID-19 cases.

Washington D.C serves as an example of a city that reported relatively high rates of participation at protests at the nation’s capital, but a low rise in COVID-19 cases during the same timeframe. Though D.C. reported about 13.7 percent participation, evidence also showed that demonstrators were more likely to wear masks, potentially being the reason behind the lower rates of COVID-19. But if there is one thing for certain, protestors are taking the risk of COVID-19 seriously, while establishing that the harm of racism is much more detrimental to public health than the protests themselves.

Systemic Racism and COVID-19

The fight against police brutality is also the fight against systemic and structural racism.

The inherent structural practices of racial exclusion, intergenerational trauma, disinvestment, and violence have hindered marginalized communities from equitable healthcare and heightened their exposure to COVID-19. As a result of the disproportionate exposure to COVID-19, Black Americans have been dying at higher rates from the virus than White Americans. According to the, American Public Media Research Lab, if Black Americans died of COVID-19 at the same rate as White Americans, then 21,800 Black Americans would still be alive today. However, what’s more alarming is that the overall mortality rates White Americans have experienced this year with COVID-19 is still significantly less than the mortality rates that Black Americans have experienced every year.

Dr. Camara Jones, epidemiologist and pediatrician, has attributed these disproportionate trends in COVID-19 mortality rates to manifestations of “inherited disadvantages” rather than “inherited disease”. In her words, “Race doesn’t put you at higher risk [of COVID-19]. Racism puts you at a higher risk.” The inherited disadvantages refer to the embedded racist laws and policies which advantage some racial groups that seem “superior” while disadvantaging those that seem “inferior”. Whereas, inherited disease refers to the biological factors and individual behaviors that seem to contribute to illness. Dr. Jones argues that instead of focusing on how inherited diseases contribute to COVID-19, individuals should focus on how structural racism and differential access to the social determinants of health (educational opportunities, income level, housing, food security, and access to healthcare) disadvantage and harm the overall health of communities, even more so during the pandemic.

If we take a look back at D.C, the city that reported relatively high rates of participation in protests, we can also see the impact “inherited disadvantages” such as residential discrimination has had on the health of Black communities, pre-pandemic and during it as well. In D.C., Black Americans are dying of COVID-19 at a rate four to six times higher than White Americans are dying above their population share. According to a study last year reported by the University of Minnesota, “low-income residents are forced out of the District by high housing prices and other pressures, and they often move into similarly distressed neighborhoods in Maryland or Virginia.” Relatively distressed neighborhoods are more likely to expose individuals to poor environmental conditions such as heightened levels of toxic waste or air pollution. Long term exposure to common air pollution has been associated with a 15% increase in COVID-19 mortality rates. The inherited disadvantages further hinder individuals from practicing safe measures to prevent COVID-19. For example, residential discrimination causes Black communities to be about twice as likely to lack access to clean water, which makes a critical public health intervention such as hand-washing more difficult as well, once again disproportionately shaping the distribution of COVID-19.

Protesting as An Effective Public Health Intervention

Protesting is a vital and powerful public health intervention because as pediatrician Dr. Rhea Boyd said “Protesting is one of the most important mechanisms by which equality is advanced in this country.” Protests save lives through advancing laws, redefining social norms, and crafting equitable policies that intend to end all forms of racism and inequity in this country. According to Dr. Elliey Murray, assistant professor of epidemiology at Boston University School of Public Health, “Public health messaging has always been about how to minimize harm. Harm reduction is the core of public health.” The Black Lives Matter Movement minimizes harm by calling out the injustices of police brutality along with bringing to attention the ways in which the pandemic has left Black communities more vulnerable to contracting COVID-19. Therefore, the protests align with the purpose of public health interventions as they seek to improve the physical, emotional, and mental health of their communities.

Drawing from historical movements, such as the Black Panther Party, we also see the direct impact social movements and protests have had in addressing health inequities. In Alondra Nelson’s book Body and Soul: The Black Panther Party and the Fight Against Medical Discrimination, she documents how the Black Panthers built health resources for the Black Community while demanding accountability from healthcare providers.

Similarly today, we see that Black Lives Matter Movement has created an environment of national reckoning, in which lawmakers are slowly starting to recognize the importance and demand for immediate change. Following the protests in June, officials in more than 20 cities and counties and three states, Wisconsin, Ohio, and Michigan, voted to declare racism a public health emergency. By declaring racism as a public health crisis, cities, counties, and states are starting to reallocate resources and spur change across all sectors of government, ranging from criminal justice, policing, education, housing, transportation, taxes, economic development, and social services in order to close the gap that exists within access to the social determinants of health. However, these declarations are long overdue and the government committing to addressing issues of systemic racism is just the start.

Why Protest Now?

So why protest now? Some have asked can’t the protests wait until later? The simple answer: no, the protests cannot wait until later. Regardless of who we are, our background, our identity, or where we come from, we have the responsibility to stand up for our Black brothers and sisters across the entire nation. We cannot sit idly during a pandemic and wait until afterwards to demand justice and change. Police brutality coupled with racism and the pandemic has taken away the lives of countless Black Americans. As Naomi Thyden, MPH, a PhD student in epidemiology at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health said, “We have a choice to either watch the health and safety of Black Americans get worse and worse as this pandemic progresses, or we have the choice to say we’re not going to tolerate it anymore.” As a society, we need to make sure our voices are heard and we need to stand up and say we’re not going to tolerate this anymore. Racism affects us all. Furthermore, standing up and fighting for the health of Black communities paves the way to ensure rights and justice for other communities of color as well. It may seem inconvenient to protest during a pandemic, but the time will never be right to protest and demand change. The time to demand change is now.

What can we do? Who should we call on to be advocates? Can change really be made?

Protesting is powerful. There is nothing greater than the collective voices of thousands calling for change and the abolition of racism in society. That’s why the Black Lives Matter Movement has now become one of the largest movements in US History. As a result of the protests, racist relics have been removed, certain cities are looking into police reform, various organizations have apologized for their inherent racist biases, and individuals have begun to realize their privilege and question the normative whiteness that has embedded society. This is only the beginning, and there is still so much work that needs to be done. Protesting may not be the complete answer to ensuring health equity, but it is the first part of the solution in implementing long-lasting and progressive change that will positively affect the health of communities for generations to come.

Though to some it may seem as if the protests died down, countless individuals to this day are still out on the streets calling out “No Justice. No Peace.” Even if we do not partake in the protests, we all have a responsibility to advocate and call out the racism that is still ever present within our own communities. Within our own communities, we can start by questioning our own internal biases and prejudices, supporting mutual aid efforts, donating to bail funds, signing petitions, calling your representatives, and doing everything you can to end racism once and for all.

List of Anti-Racism Resources:

- Actions You Can Take

- A COVID-19 Cultural Strategy Guide for Activists and Artists PDF

- Decolonize Your Mind: List of Books, Podcasts, and Movies

Edited by: Sumayyah Farooq

Естественное дело, Ваша статья стоит внимания. Однако, хочется намного больше деталей.

LikeLike

Никогда не размышляли, что на Вашем портале настолько немало полезной информативной выборки

LikeLike

Fantastic post but I was wanting to know if you could write a litte more on this subject? I’d be very thankful if you could elaborate a little bit more. Cheers!

LikeLike

I’ve been exploring for a little bit for any high quality articles or blog posts on this sort of area . Exploring in Yahoo I at last stumbled upon this website. Reading this information So i’m happy to convey that I’ve an incredibly good uncanny feeling I discovered just what I needed. I most certainly will make certain to don’t forget this website and give it a glance on a constant basis.

LikeLike