Written by Maddie Dietl and Catherine Xu

In the past month of March, Sarah Everard has become one of the most prominent names from the UK. After being last seen on March 3rd, 2021 walking back to her home in Brixton Hills, London, Everard was reported missing by her boyfriend, who contacted the police after she did not meet him. Then, on March 10th, 2021, her body remains were found near Ashford, Kent, ultimately confirming that she was kidnapped and then brutally murdered. Sarah Everard’s case has shined light to an ongoing problem in the UK: neglect of violence against women by the police. The fact that the suspect was a police officer and the aggressive behavior from the police officers towards the organized vigils for Ms. Everard has confirmed how inadequate the police system is against violence against women. Instead, feminist groups across the UK have been developing a national movement over the past month, calling for explicit legal accommodations from the government to secure women’s safety.

With March being Women’s History Month, the fury towards the police system’s neglection of violence against women has spread across the globe, starting an important conversation. Using hashtags and messages such as “Maybe not all men, but all women;” “Break the silence on male violence;” and “Take back the night”, women have been able to share their stories about experiences with sexual assault and domestic abuse through social media. The widespread similarities that women across the globe face with violence ultimately reinforces the idea that their stories are not just a mere coincidence but, rather, a public health issue. Since 2005, when the first results of the World Health Organization Study on Women’s Health and Domestic violence came out, the amount of research on violence against women has increased. Many studies have found that the cumulative impacts of violence against women on health are greater than more commonly accepted public health issues. For example, in Victoria, partner violence was found to have accounted for 7.9% of the overall disease burden among women of reproductive age, even ranking higher than other health risks, such as raised blood pressure, tobacco use, and increased body weight.

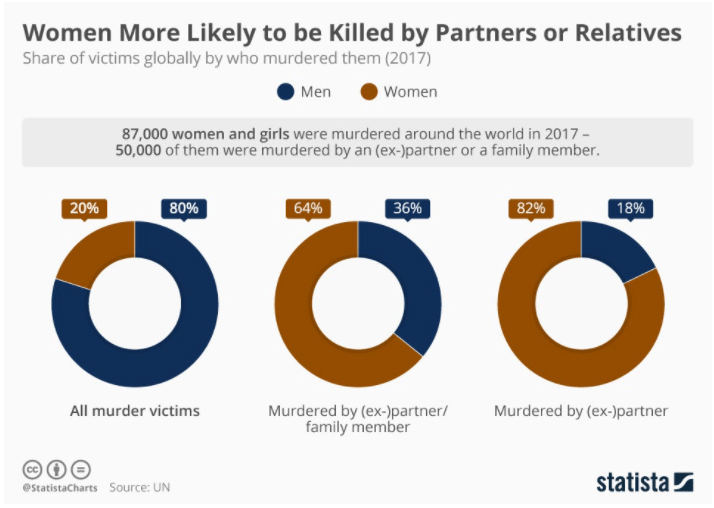

Violence against women is nothing new. On average, six women are killed every hour by men, which adds up to around 80,000 a year. While men make up a higher percentage of total homicides, over 80% of domestic violence deaths are women. In 2018, an analysis by the World Health Organization (WHO) found that worldwide, nearly 1 in 3 women have been the victim of abuse at the hands of a domestic partner. WHO lists many causes as factors in this staggering statistic, including “lower levels of education, a history of exposure to child maltreatment, witnessing family violence, community norms that privilege or ascribe higher status to men and lower status to women, low levels of women’s access to paid employment, and low levels of gender equality.” Women who have been abused in the past are also likely to choose abusive partners in the future, creating a cycle that is hard to escape. Furthermore, the pandemic has exacerbated domestic violence even more; 54% of women surveyed by CARE in Lebanon reported increased violence and harassment during the pandemic, domestic violence reports rose by 30% in France and intrafamily violence against women aged 29-59 spiked 94% between March to May of 2020 in Colombia.

High rates of violence, and even the threat of violence, contribute to the overall strain that women face in a patriarchal world every day. In an interview with Professor David Skubby, a sociology professor at the University of Virginia, he says that “we can certainly argue that women can face more chronic strains than men. Look at workplace sexual harassment, look at the home life, where women are more often victims of all kinds of abuse, whether it be emotional, mental, or physical.” The term “allostatic load”, coined by Bruce McEwen in 1993, is defined as “the wear and tear on the body which accumulates as an individual is exposed to repeated or chronic stress”. Women have been found to have a higher allostatic load than men, especially for poor women and women of color. Professor Skubby speculates that “issues that produce chronic strain,” such as violence and the threat of violence, combined with women not having the social resources to deal with problems relative to men lead to women having to “maintain a higher allostatic load”. This leads to women being vulnerable to and experiencing illness more often, which also contributes to something that caught the eye of researchers in the 19th century and was coined the “gender paradox”, where women experience higher rates of sickness and chronic disease, yet live longer than men.

The question is, how does violence contribute to a woman’s health over the course of her life? Physical and sexual violence have been linked to greater mental health issues among women, including higher rates of depression, sleeping and eating disorders, stress and anxiety disorders (e.g. posttraumatic stress disorder), self-harm and suicide attempts, and poor self-esteem. Women affected by violence can also develop behavioral issues down the line, like harmful alcohol and substance use, choosing abusive partners later in life, lower rates of contraceptive and condom use, and problems refusing unwanted sexual advances.

These days, the term “rape culture” is frequently mentioned when discussing stories of sexual assault. It is used to explain how violence is normalized and excused in a culture where society is desensitized, often through pop culture media, to sexual assault on women.

“Rape culture is a culture in which sexual violence is treated as the norm and victims are blamed for their own assaults. It’s not just about sexual violence itself, but about cultural norms and institutions that protect rapists, promote impunity, shame victims, and demand that women make unreasonable sacrifices to avoid sexual assault.”

Rape culture includes things such as “locker room talk” and the saying “boys will be boys”, and takes away responsibility from those committing the assault and puts it on to the victim. Pop culture media often perpetuate this culture, especially modern music and internet culture. A male-dominated government and legislative body also can contribute to this culture when women’s bodily rights and protections are taken away through laws prohibiting abortion, taking away protections for victims of sexual assault, and allowing people accused of sexual assault to take office. Professor Skubby proposes that having more women in leadership positions, both politically and economically, is one step towards equality that will “diminish the prevalence of rape culture”. Strides have been made to achieve this in the past few years, and the most recently elected Congress is the most female-heavy ever.

Talking about the issue of violence against women is just the first step in making the world a safer place for everyone. To fight this epidemic, people need to step up and responsibility needs to be taken. Women cannot fight this alone, so it is up to everyone to do their part not only for people like Sarah Everard, but for every woman who has ever felt unsafe walking home alone at night. The culture surrounding sexual assault is shifting, and attention is needed now more than ever to ensure that it doesn’t return to a state of acceptance and normalization. For the current and future health and safety of all women, we all need to step up.

A great post without any doubt.

LikeLike

Good day I am so glad I found your site, I really found you by mistake, while I was searching on Aol for something else, Regardless I am here now and would just like to say thanks for a fantastic post and a all round enjoyable blog (I also love the theme/design), I don抰 have time to look over it all at the moment but I have saved it and also added your RSS feeds, so when I have time I will be back to read a lot more, Please do keep up the great work.

LikeLike

whoah this blog is great i love reading your posts. Keep up the great work! You know, many people are searching around for this information, you could help them greatly.

LikeLike

Nice i really enjoyed reading your blogs. Keep on posting. Thanks

LikeLike

An intriguing discussion is worth comment. There’s no doubt that that you need to publish more on this issue, it may not be a taboo matter but generally people do not speak about these topics. To the next! All the best.

LikeLike

some genuinely select posts on this site, saved to favorites.

LikeLike