Written by Kira Nagoshi and Akila Muthukumar

Introduction

Former U.S. President Donald Trump’s hostile immigration rhetoric and harsh family separation policies met a wave of public outrage in 2016-2018 as human rights violations at the U.S.-Mexico border came to light. However, this temporary spike in widespread media coverage of detention centers has dissipated in the last few years despite persistent abuse and mistreatment. Although other congregate settings, ranging from nursing homes to prisons, have caught public-health officials’ interest as a result of the coronavirus pandemic, immigration detention centers have largely been left out of public discourse and federal policy. In turn, the lack of transparency about Covid-19 and inadequate protection against viral transmission has created a severely overlooked public health crisis for the nearly 16,000 detained people in the U.S., according to a January 2021 Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) report, authored by the Harvard Student Human Rights Collaborative Asylum Clinic under the guidance of Dr. Katherine Peeler. Three collaborators on the project, Harvard Medical School students Parsa Erfani, Nishant Uppal, and Raquel Sofia Sandoval were interviewed about this work and what they learned from their interviews with formerly detained individuals. The information in this story came from these interviews, the PHR report, and additional research from sources cited through hyperlinks.

A Brief History of Detention Facilities

Unlike the long-standing history of traditional American carceral institutions that were codified in the colonial era, immigrant detention centers were constructed beginning in the 1980s. Georgetown research fellow Smita Ghosh wrote in the Washington Post that the Reagan administration responded to rising numbers of Caribbean refugees by detaining “all arriving migrants, including asylum seekers” and that conditions in these facilities were extremely unsanitary and inhospitable. In 1986, the New York Times reported that a federal detention center opened in Louisiana, co-run by the U.S. Bureau of Prisons and the Immigration and Naturalization Service (the predecessor of the Department of Homeland Security). The same report also states that at the time, there were 3,025 undocumented immigrants detained in the U.S., in facilities ranging from privately owned detention centers to county jails. The use of detention proliferated through the 1990s. By 2014 the Obama administration further expanded detention programs in response to the Central American Refugee Crisis. Similar practices and substandard treatment of detainees still prevail today, particularly as the Trump administration further expanded the network of facilities and removed existing protective policies.

Immigrant Detention Facilities and the Coronavirus

Early in 2020, the U.S. government provided very little guidance in terms of what Covid-19 safety and testing procedures should look like in different congregate settings. Though U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) released its COVID-19 Pandemic Response Requirements in October 2020, these guidelines were not fulfilled in practice. The PHR report found that living conditions do not comply with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s basic guidance on social distancing, quarantine, or even access to soap and sanitizer.

Coronavirus case rates are about 13 times higher in ICE detention centers than among the general population due to lack of accessible information, testing, and sanitation. Despite being at much lower risk (as a population), a Harvard undergraduate has access to testing 3 times a week and all Harvard Medical Students studying in-person are offered vaccines. This stark contrast illustrates the urgent need for redistribution and equitable policy. To most effectively protect public health, proper protection cannot be treated as a luxury. Pandemic mitigation should be a public, not private, movement.

Erfani, Uppal, and Sandoval were part of the team that conducted 50 interviews with people who were released from ICE detention facilities (13 private & nine county) between March and August, 2020. ICE’s negligence became apparent when interviewees shared how they were denied access to socially distant spaces, masks, testing, or special protections for high-risk individuals. Little progress occurred only after ICE faced repeated lawsuits.

When the 80 of us ate together, we were elbow-to-elbow.

27-year-old man, Tacoma Northwest Detention Center

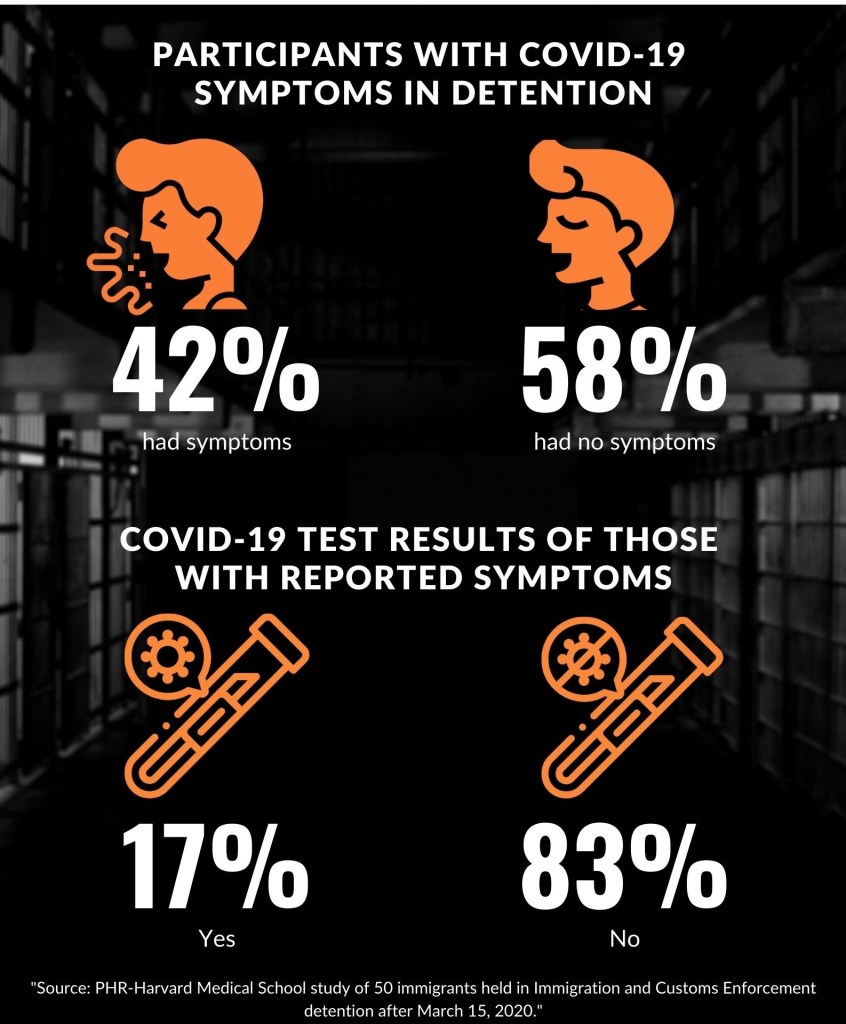

Twenty-one interviewees experienced symptoms of COVID-19 while in detention, eighteen reported their symptoms to ICE, and only three were isolated and tested, waiting for up to 4 days before seeing a medical professional. Three others mentioned not wanting to share their symptoms; Erfani explains that one of the reasons for this was fear of being placed in solitary confinement as a form of medical isolation. Prolonged solitary confinement was misused as medical isolation, inflicting additional psychological harm onto detainees.

Eighty-five percent of interviewees learned about COVID-19 from the news and had a hard time getting tested and getting treatment when they reported symptoms to detention officials. Those who protested or reported conditions faced retaliation and intimidation, including tear gas and pepper spray.

People who did not have money had to wash their hands only with water.

33-year-old man, Otay Mesa Detention Center

Further, Sandoval reflects on the experience of interviewing Spanish-speaking participants and explains that in addition to physical violence, verbal violence, and violence of isolation, signs and information — including waivers signing away rights — were often given only in English. Sandoval sees this as a double punishment for non-English speakers: not only did they not have access to much information, the information they could find was not easily understood.

She continues to explain how folks interviewed spoke about the difficulty of not only knowing there was a terrifying virus that was killing people, but that they “have no means of accessing that knowledge.”

Vaccination

Immigration center detainees are not comprehensively included in different states’ phase 2 of vaccine distribution, which is intended to cover individuals in high-risk settings like a detention center. Federal government materials do not clearly state whether immigrant detainees would be considered part of traditional incarcerated populations and thus be included in vaccination efforts.

Further, Uppal explains how operations of ICE detention centers are decentralized, making physical distribution practices nonuniform.

Specifically, he explained that in some instances, the federal government physically owns the property where the detention center exists and contracts out services to for profit companies. These private entities are put in charge of delivering health care to detained individuals. But in some reverse situations, for-profit companies own the physical property and the federal government staffs officials and operations within the facility. A combination could be true too, where the federal government or for-profit company both owns the property and is responsible for services. Finally, Uppal noted that in yet other instances, those who are in immigration detention are housed in county jails, which creates additional concerns for local jurisdictions to address.

The Reagan administration’s push for detention first introduced a federal collaboration with private prison contractors like the Corrections Corporation of America (now CoreCivic) that run and profit from detaining immigrants. Now, about 70% of people in ICE detention are housed in privately contracted facilities (the major players being Geo and Core Civic).

Given this complexity, prioritizing standardized and nationwide policy solutions is optimal. Federal governments obtain vaccines from pharmaceutical companies and this supply can be requested by healthcare systems and state governments. Federal agencies can also apply for vaccines via a separate designation as federal entities and thus, ICE or the DHS could use this route to obtain and distribute vaccines to detainees.

Potential & Limitations of Policy Solutions

Abhorrent living conditions, blatant disregard for public health, and gaps in vaccine distribution can be tackled, in part, with policy. The Fifth Amendment and the UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners mandate due process and healthcare for detainees.

Beginning at a federal level, Biden has signed an order to not renew contracts for for-profit prisons and jails, but only 8-9% of the incarcerated population in the United States is in private facilities. Even with the order in place, mass incarceration remains a prevalent human rights issue and to preemptively celebrate or settle for slow progress would be a disservice to criminal justice advocacy.

Further, though he made promises on the campaign trail to also act on immigration detention, the Biden administration has not yet released such legislation. Late January 2021, he was “considering” a separate executive order addressing immigration detention centers that parallels the one that’s already passed on carceration.

A more concrete piece of legislation includes the New Way Forward Act that Democratic U.S. Rep. Jesus “Chuy” Garcia of Illinois proposed. This Act addresses both combinations of federal and private detention centers as opposed to Biden’s executive orders on carceration, which only focused on the for-profit institutions.

Although Congressional policy decisions have the practical potential to improve living conditions for detainees, advocacy cannot be restricted to government policy. Long-term abolition would look like a complete rejection of all institutions responsible for structural inequities. As proposed by a number of prominent politicians in recent years, including former presidential candidate and Mayor of San Antonio Julián Castro, we should decriminalize illegal border crossings and explore alternatives to detention.

Immigration detention should move towards case management, devoting resources to help an underserved population integrate into our communities. Regarding compliance concerns, the U.S. Government Accountability Office found that between 2011 and 2013, ninety-five percent of the participants in their “full-service” Alternative to Detention (ATD) program, which includes case management, appeared for their final hearing. Another similar ATD program, the Family Case Management Program (FCMP), was shut down in 2017 despite showing similarly high efficacy and compliance rates. Many case management services are currently offered by community organizations, not local or federal government agencies, but evidence from existing ICE programmes demonstrates the efficacy of more humane alternatives to detention.

Advocacy and the Future

Despite former President Trump’s false typecasting of immigrants as criminals, Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) reports that most civil detainees held by ICE do not have a criminal conviction and are instead only being held to wait for civil immigration proceedings. The same report notes that less than 6,000 detainees nationwide of them had a serious criminal conviction (as labeled by ICE) on record. Uppal points out the odd contradiction: how do for-profit immigration entities detain individuals who have not been accused of a crime when a similar policy would be unheard of for most civil offenses in the United States?

People can present themselves at the U.S. border as asylum seekers, and their first experience can be detention… they’re essentially put into a prison system in which they can choose to work in a voluntary work program for $1 a day in order to buy the necessities they need to survive in that institution.

Parsa Erfani

Innocence aside, detained immigrants deserve better conditions not just because they have not committed criminal offenses, but because respect, safety, and dignity is owed to all people regardless of criminal or citizenship status. Erfani explains that comparisons between traditional criminal incarceration and immigration detention should not detract from the importance of convicted individuals being “paid for the labor they provide in a fair and just way” and being “guaranteed their health and human rights.”

As such, the movement against immigrant detention works in tandem with the decarceration movement. While decarceration and abolishing detention are absolutely long term goals of the group’s work, Sandoval notes that “in the meantime, it is so important… to advocate for humane conditions and treatments” and to protect the safety and health of detainees on the way to accomplishing decarceration on a wider scale.

While the Biden administration and the work of progressive Congress members provides hope for progress, it is important to remember that the voices and rights of incarcerated individuals are taken away from them. To move towards a more just, equitable, and humanistic future, it is imperative that the concerns of marginalized populations, like those in detention centers, are not only heard from but uplifted, and the systems that facilitate oppression are deconstructed.

Edited by Haruka Margaret Braun

I seriously love your website.. Pleasant colors & theme. Did you make this web site yourself? Please reply back as I’m attempting to create my own site and would like to know where you got this from or exactly what the theme is named. Thanks!

LikeLike

Hello! We’re an intercollegiate organization and a team of 60+ students, and you can learn more about us on the “Our Team” page. The theme we are using is called “Canard.”

LikeLike

Very good information. Lucky me I found your blog by chance (stumbleupon). I have bookmarked it for later!

LikeLike

Hello I am so excited I found your webpage, I really found you by error, while I was researching on Yahoo for something else, Nonetheless I am here now and would just like to say thank you for a remarkable post and a all round entertaining blog (I also love the theme/design), I don’t have time to read through it all at the minute but I have saved it and also added your RSS feeds, so when I have time I will be back to read much more, Please do keep up the fantastic job.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Woah! I’m really enjoying the template/theme of this site. It’s simple, yet effective. A lot of times it’s very hard to get that “perfect balance” between user friendliness and visual appeal. I must say that you’ve done a amazing job with this. In addition, the blog loads very quick for me on Safari. Exceptional Blog!

LikeLike